105. Deep Research on Fun Creation with AI

If you have not used OpenAI's Deep Research feature you are missing out! I just used it for the first time on a topic you might be familiar with. I asked it the following:

"Fun and Meaning are not properties of the action required but a way of thinking by the mind performing the action. I want research that studies how people make seemingly unfun activities fun and what their theory of fun creation is."

It took 8 minutes and went through 33 sources.

Its answer is below. Brace yourself. It is amazing!

I'll look into research that explores how people turn seemingly unfun activities into enjoyable ones, including psychological mechanisms, cognitive reframing, and theories of fun creation. Expect insights from cognitive psychology, behavioral science, and philosophy.

I'll update you when I have the findings ready.

Turning “Unfun” Activities into Enjoyable Ones

People often face tasks that feel boring, tedious, or unpleasant – yet research shows we can transform such “unfun” activities into enjoyable experiences. Psychologists, behavioral scientists, and even philosophers have explored how mindset, motivation, and meaning can make a dull chore engaging or even fun. Below, we break down key theories, studies, and strategies for creating fun out of the mundane, along with practical takeaways.

Cognitive and Psychological Mechanisms of Fun Creation

Reframing and Mindset Shifts: How we think about an activity greatly affects our enjoyment. For example, classic research on cognitive dissonance found that people convinced themselves a boring task was actually fun when they lacked an external reward. In a 1959 experiment, participants did a dull task (turning pegs) and were paid to tell the next person it was enjoyable. Strikingly, those paid only $1 (minimal reward) later reported the task as far more enjoyable than those paid $20 (large reward) (The Boring Task. Taking Control of Mental Discomfort | by Valkyrie Holmes | students x students). With only a small incentive, they “reframed” the experience as fun to justify their efforts, illustrating how attitude adjustment can create genuine enjoyment. Modern approaches encourage reframing dreaded tasks in a positive light – for instance, viewing doing taxes as “getting a refund” or exercise as “well-deserved me-time”. This kind of cognitive reappraisal can reduce procrastination and increase motivation (How to make tedious tasks more tolerable | UBC Magazine) (How to make tedious tasks more tolerable | UBC Magazine).

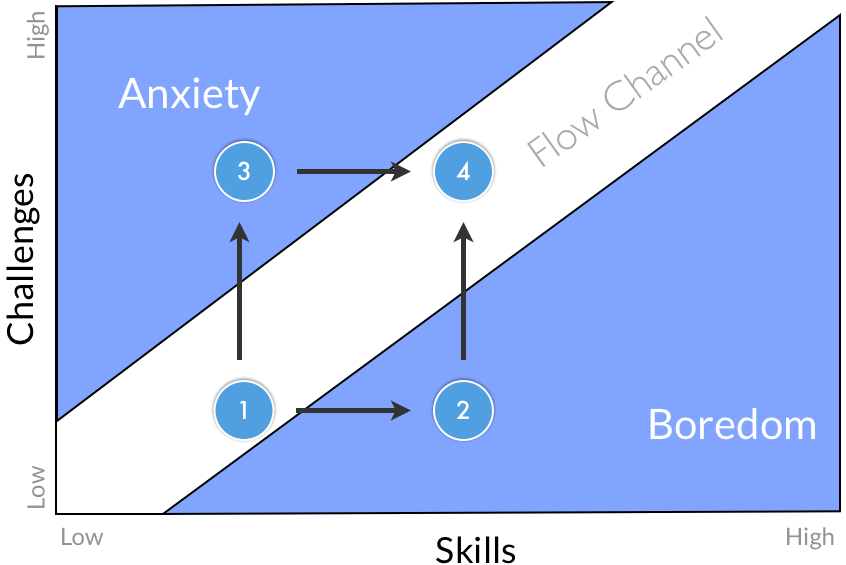

Flow State and Optimal Challenge: Psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s flow theory explains that activities become deeply enjoyable when we reach a flow state – total immersion in a task. Flow happens when the challenge of an activity is balanced with our skill level, so that it’s neither too easy (causing boredom) nor too hard (causing anxiety) (What’s in a game?). In this sweet spot, time seems to fly and the work feels rewarding in itself. (In fact, Csikszentmihalyi called such experiences “autotelic,” meaning done for their own sake, as opposed to “exotelic” activities done for an external reward (What’s in a game?).) By adjusting a task’s difficulty to fit our skills or vice versa (for example, by setting a personal challenge to spice up a simple chore, or by acquiring new skills to handle a tough job), we can trigger a flow state. Flow is characterized by clear goals, immediate feedback, and a sense of progress, which make the activity intrinsically satisfying. Many people have experienced flow during hobbies, sports, or video games – and the same concept can apply to work and chores when approached with the right level of challenge.

(What’s in a game?)According to flow research, we are happiest when tackling tasks that hit the right degree of difficulty. Too easy and we disengage; too hard and we stress out. Fun emerges when we feel challenged but capable. This diagram illustrates the “Flow Channel,” the zone where one’s skill matches the challenge at hand, between boredom and anxiety:

(How to 'Flow': Here’s the most magical chart you’ll come across today) Flow Channel: Tasks are most enjoyable when challenge level (vertical axis) and skill level (horizontal axis) are in balance. In this state of flow, attention is fully absorbed and the activity feels rewarding (What’s in a game?).

“Gamifying” the Task: Another cognitive strategy is to add game-like elements or a playful mindset to an otherwise dry activity. Games are fun largely because they provide clear goals, feedback, little rewards, and a sense of progress. Even small wins give our brains a dopamine boost, reinforcing our motivation (How to make tedious tasks more tolerable | UBC Magazine) (How to make tedious tasks more tolerable | UBC Magazine). We can mimic this by breaking a task into smaller sub-tasks and celebrating each completion. Research by neuroscientist Dr. Catharine Winstanley notes that dividing a chore into a series of small steps “tricks your brain into feeling accomplished when you complete each ‘chunk’,” effectively “teasing your motivation system” with frequent, low-effort rewards (How to make tedious tasks more tolerable | UBC Magazine) (How to make tedious tasks more tolerable | UBC Magazine). Each crossed-off mini-goal triggers a small dopamine hit and momentum to tackle the next part. In essence, you’re turning the task into a game of achievable checkpoints. Many people also introduce arbitrary challenges or rules to make an activity playful (for example, racing against the clock to clean a room, or turning learning into a quiz for points). This “lusory attitude” – willingly adopting unnecessary challenges as if one were playing a game (Lusory attitude - Wikipedia) – can inject fun into the most routine duties.

Mindset of Growth and Mastery: Sometimes a task isn’t fun because we see no point in it beyond the outcome. Adopting a learning or mastery mindset can help. If you view an unexciting activity as an opportunity to practice a skill or build character, the process itself gains value. Psychologists note that an intrinsically motivated mindset – focusing on the interest or growth in the task – makes it more enjoyable and sustainable than just thinking about external rewards. Even simply choosing to smile or be light-hearted during a task can improve mood and make it feel more like play. Workplace trainers often cite the FISH! Philosophy, which encourages bringing a playful attitude to everything you do: “If work is what you have to do, then play is how you do it.” In other words, you can be serious about your goals but still approach the process with humor, creativity, and curiosity (The Importance of Fun at Work). This kind of mindset shift – treating work as play – often leads to greater enjoyment and even better results.

Intrinsic vs. Extrinsic Motivation in Perceiving Fun

Intrinsic Motivation – Doing it “for its own sake”: Activities we find fun are usually driven by intrinsic motivation – we do them because we enjoy the activity itself (the means), not just for some external payoff (the end). For instance, playing a sport or a video game just for the pleasure and challenge is intrinsically motivated. Csikszentmihalyi described such enjoyable, self-driven activities as autotelic (from Greek auto = self, telos = goal) – “activities you want to do for their own sake, as opposed to exotelic activities done for a reward” (What’s in a game?). When we tap into intrinsic motivation, even hard work can feel like fun because we’re internally fulfilled – be it through interest, personal meaning, or a sense of accomplishment. One way to increase intrinsic motivation is to connect an unfun task to your core values or goals. For example, someone who values health might find meal prepping more enjoyable by viewing it as part of their fitness journey. If a task aligns with something you care about (growth, helping others, creativity, etc.), your internal satisfaction grows.

Extrinsic Rewards – Useful Boost or Double-Edged Sword: On the other hand, extrinsic motivation relies on outside rewards (pay, prizes, grades, praise). Adding an external reward or incentive can sometimes make a dull task enticing – e.g. promising yourself a treat after finishing paperwork, or kids earning points for doing chores. Behavioral science shows that rewards and gamification can increase engagement, especially for tasks that weren’t fun to begin with. For instance, incentivizing exercise with money or prizes reliably boosts gym attendance in the short term ( Holding the Hunger Games Hostage at the Gym: An Evaluation of Temptation Bundling - PMC ). Even small “token” rewards like badges, points, or leaderboards can spark motivation by appealing to our competitive or achievement drive. However, extrinsic rewards should be used with care. According to the overjustification effect, if you heavily reward someone for an activity they already find intrinsically enjoyable, their natural interest can diminish (Overjustification effect - Wikipedia). In other words, they start doing it “for the reward” and lose some of the original fun. A classic demonstration of this: children who loved drawing with magic markers lost interest when they began receiving prizes for drawing, as the activity started to feel like work instead of play. The key is to use extrinsic motivators to kickstart engagement or add excitement, but gradually let intrinsic enjoyment take over.

Self-Determination and Basic Needs: Intrinsic enjoyment often comes when an activity satisfies our basic psychological needs – autonomy (choice/control), competence (mastery/progress), and relatedness (social connection). This is the basis of Self-Determination Theory. If you can tweak an unfun activity to satisfy these needs, it will likely feel more fun. For example: giving yourself autonomy in how or when you do a chore (making it a personal choice or game) increases enjoyment versus feeling forced. Finding ways to track improvement or skill in the task can enhance your sense of competence (e.g. timing how fast you mow the lawn and trying to beat it next time turns it into a skill challenge). Even making a solitary task social – like doing housework alongside family or turning it into a friendly competition – can fulfill the need for relatedness and make it more enjoyable. In gamification studies, tasks that support autonomy, competence, and social relatedness have been found to sustain motivation better than those that only give superficial rewards (Game on: Can gamification enhance productivity? - F1000Research) (Case Studies of Successful Gamification Initiatives in Professional Development Programs ). In short, intrinsic fun blooms when we feel ownership, achievement, and connection in what we’re doing.

When External Becomes Internal: Interestingly, extrinsic and intrinsic motivation aren’t entirely separate poles; they can interact. A initially external reward can, over time, become internalized as part of the enjoyment. For instance, a person might start running only to win a prize (extrinsic), but then begin to love running for its own sake – the thrill of improving and the runner’s high (intrinsic). Good gamification design tries to facilitate this by first hooking you with points or challenges, but eventually you find the activity itself rewarding beyond the points. On the flip side, if a task is extremely unfun at the start, a small extrinsic reward can be that nudge to get you going – and once you’re engaged, you may discover aspects of it that are interesting. Behavioral economists have even used “temptation bundling” to merge extrinsic and intrinsic motivations: for example, only allowing yourself to enjoy a guilty pleasure (say, bingeing a favorite podcast) while doing the unpleasant task (like cleaning). This way, the fun part boosts your desire to do the unfun part ( Holding the Hunger Games Hostage at the Gym: An Evaluation of Temptation Bundling - PMC ). (In one study, participants who could only listen to their beloved audio novel at the gym ended up exercising more, and 61% of them wanted to keep this system after the experiment – they had effectively made the gym fun by associating it with a treat ( Holding the Hunger Games Hostage at the Gym: An Evaluation of Temptation Bundling - PMC ).) The goal is often to train your brain to associate the “grind” with something positive, so eventually the activity itself isn’t dreaded. Over time, as you gain skill or see results, the intrinsic rewards (satisfaction, pride, meaning) take center stage.

Case Studies and Experiments: Making the Mundane Fun

Real-world examples across various domains show how adding fun or altering perception can change our behavior and attitude toward “unfun” tasks:

- The Piano Stairs Experiment (Volkswagen’s Fun Theory, 2009): An ordinary subway staircase in Stockholm was transformed into an interactive piano – each step played a musical note when stepped on. The result? Commuters started choosing the stairs in droves. In fact, 66% more people than usual took the stairs over the escalator once it became a giant piano (The Piano Stairs Experiment: Making Life More Fun | Academy 4SC). This lighthearted intervention vividly demonstrated “fun is the easiest way to change people’s behavior for the better.” Climbing stairs, normally seen as effortful, turned into an entertaining game (making music as you walk). Many who normally avoided the exercise found that the enjoyment offset the extra effort (The Piano Stairs Experiment: Making Life More Fun | Academy 4SC). The Piano Stairs became a viral example of how novelty and playfulness can reframe a dull activity (walking up stairs) as a fun experience, encouraging healthier behavior without force.

(The Piano Stairs Experiment: Making Life More Fun | Academy 4SC) (The Piano Stairs Experiment: Making Life More Fun | Academy 4SC)One famous result from the Piano Stairs: simply by making a task fun, more people did it. (See image below of a piano-themed staircase.)

(File:Polanco's staircase.jpg - Wikipedia) Figure: A subway staircase painted like piano keys (an implementation of the Fun Theory). In the experiment, such piano stairs led to 66% more commuters taking the stairs instead of the escalator by making the activity playful and musical.

- Gamified Exercise – “Zombies, Run!” and Pokémon GO: Exercise can be a classic “unfun” activity for many. Enter gamification. The app Zombies, Run! turns jogging into an immersive game where you’re a hero in a zombie apocalypse story, collecting supplies and evading zombies. This narrative trick – making your run feel like a mission – has made running addictive for over a million players, many of whom report they forget they’re even exercising because they’re so engaged in the story. Similarly, Pokémon GO (the augmented reality game) in 2016 got millions of people worldwide to happily walk outside to catch virtual creatures. A study in the Journal of the American Heart Association found that players walked an extra ~2,000 steps per day on average while playing Pokémon GO (Pokemon Go boosts physical activity, particularly among those who need it the most | Duke University School of Medicine). The percentage of those achieving 10,000+ steps a day (the recommended activity level) nearly doubled among players during the craze (Pokemon Go boosts physical activity, particularly among those who need it the most | Duke University School of Medicine). Though the effect was not permanent for everyone, it showed how layering a fun goal onto walking (catching Pokémon, exploring locations) motivated people to be more active. In both cases, unfun exercise became fun by tapping into our love for games, stories, and collection challenges.

- Chores and Habit Gamification – The Chore Wars: Even household chores have been successfully gamified. A website called ChoreWars (and many chore apps since) lets family members or roommates compete for points and badges by doing housework (slaying the “Laundry Monster” or conquering the “Dishwashing Dungeon,” for example). Families reported that kids who once dodged chores started actively volunteering for them, just to gain points or beat siblings in the game. One could achieve similar effects at home without an app: e.g., make a sticker chart for tasks completed or turn cleaning into a timed challenge. The key is adding competition, rewards, and fantasy to otherwise bland tasks to change the mindset from “I have to do this” to “I get to play this.” While these approaches are often extrinsically motivated at first (who doesn’t want to win a game?), they tend to work especially well for tasks that no one inherently enjoys, by providing a new source of engagement.

- Workplace Gamification – Productivity Boosts: Companies have implemented game elements at work with impressive results. For example, call centers and sales teams have introduced leaderboards, achievement badges, and “level up” progress charts to make hitting targets more fun. A study by the University of Colorado found that organizations using gamified training saw a 48% increase in employee engagement and 34% increase in productivity compared to those using traditional methods (Case Studies of Successful Gamification Initiatives in Professional Development Programs ). Salesforce’s Trailhead platform (which uses badges and quests to teach skills) attracted over 1.5 million users, significantly improving skill uptake and job satisfaction among employees (Case Studies of Successful Gamification Initiatives in Professional Development Programs ). Deloitte, another case, gamified its employee training and saw completion times drop by 50% because staff were more eager to finish modules and earn rewards (Case Studies of Successful Gamification Initiatives in Professional Development Programs ). These examples show that even in serious contexts, adding elements of choice, progress tracking, competition, and reward can transform drudgery into something engaging. When work feels like a game, people often report experiencing flow and camaraderie, rather than boredom.

- Serious Games Solving Serious Problems: Fun can even tackle scientific challenges. Foldit, an online puzzle game about protein folding, invited the public to compete in solving biochemistry problems. In 2011, Foldit players famously cracked the 3D structure of an AIDS-related enzyme in just 10 days – a puzzle that had stumped scientists for 15 years (Foldit - Wikipedia). The gamers, driven by curiosity and competition, essentially turned a hard scientific task into fun, outperforming algorithms and experts through puzzle-solving gameplay. Their solution was accurate enough to be used in developing new medical treatments, showing how making a task game-like can unleash motivation and creativity at massive scales. Another citizen science game, EyeWire, turned neuron mapping into a competitive game and attracted hundreds of thousands of participants to do hours of brain-mapping “for fun,” contributing to real neuroscience research. These cases illustrate a powerful principle: when a task (however complex) is presented as a fun challenge or game, people will volunteer their time and effort gladly, achieving things that coercion or payment might not accomplish as effectively.

- Social Experiments – The Fun Theory Campaign: Beyond the piano stairs, Volkswagen’s Fun Theory campaign tried other whimsical experiments: a trash bin that made a comic “bomb dropping” sound when litter was tossed in (making people laugh and encouraging use), and a “speed camera lottery” where safe drivers were automatically entered into a cash prize lottery funded by fining speeding drivers (The Fun Theory - A Simple Way to Motivate Others). The lottery approach made obeying the speed limit fun and saw the average speed drop on that road. These playful interventions acted as case studies in behavioral science, reinforcing how fun and novelty can nudge behavior change more effectively than mere instructions or warnings. The underlying lesson: many activities (throwing out garbage, driving safely) can be boosted by introducing an element of enjoyment or positive feedback.

Philosophical Perspectives on Fun and Meaning in Activities

Beyond labs and practical hacks, philosophers have long considered what makes life’s activities meaningful or enjoyable:

Camus and the Absurd – Finding Joy in Sisyphus: Albert Camus, the French existentialist, famously concludes The Myth of Sisyphus with the line: “One must imagine Sisyphus happy.” (Existential Comic: We Must Imagine Sisyphus as Having a Hard Time Readjusting to Civilian Life | HighExistence) Sisyphus, condemned by the gods to roll a boulder up a hill on repeat forever, symbolizes the absurdity of human labor. Camus argued that even in a seemingly meaningless, endless task, we can choose our attitude. Sisyphus, fully aware of the absurdity, can “recognize the futility of his task” yet revolt by embracing it – finding contentment in the struggle itself (Existential Comic: We Must Imagine Sisyphus as Having a Hard Time Readjusting to Civilian Life | HighExistence) (Existential Comic: We Must Imagine Sisyphus as Having a Hard Time Readjusting to Civilian Life | HighExistence). In Camus’s view, meaning (and a form of happiness) comes from how we approach our labors, not from the labors themselves. This suggests that if we accept even repetitive or “pointless” tasks as part of our existence and decide to own them, we can find a sort of joy or peace. It’s a philosophical stance that resonates with making unfun tasks tolerable: by reframing the necessity of work as “the struggle itself is enough to fill a man’s heart,” we reclaim agency and even happiness in doing what must be done (Existential Comic: We Must Imagine Sisyphus as Having a Hard Time Readjusting to Civilian Life | HighExistence). It’s not “fun” in the playful sense, but it’s a profound mindset shift to find satisfaction in the very act of effort, much like a laborer taking pride in a job well done no matter how small.

Play as Fundamental (Huizinga & Suits): Johan Huizinga, in Homo Ludens, suggested that play is a foundation of human culture and a natural behavior – humans (and animals) are “innately playful” and often engage in activities just for enjoyment. He noted that play is “its own justification”: we don’t need an external reason to play; having fun is reason enough (Homo Ludens: The Nature of Play - Communications & Society). From this perspective, fun and meaning don’t always need to be tied to utility. We can allow ourselves moments of play in any context and that in itself enriches life. Building on this, philosopher Bernard Suits defined games and play in a striking way: “Playing a game is the voluntary attempt to overcome unnecessary obstacles.” (Lusory attitude - Wikipedia) In other words, in play we willingly take on challenges that we could otherwise avoid, for the sake of the experience. This definition highlights that the structure of fun often involves obstacles and mastery, but ones we choose. If we carry this idea into daily tasks, it implies that by viewing a task as a game – a set of challenges we voluntarily take on – we transform our perspective. For example, one might see doing housework as akin to completing quests or see a work project as a puzzle to solve. Suits would argue that the “lusory attitude” (game-playing mindset) is key: it’s about embracing rules or challenges playfully rather than grudgingly (Lusory attitude - Wikipedia) (Lusory attitude - Wikipedia). By making a game of our work, we create an internal narrative that can give even trivial tasks a sense of purpose and enjoyment, much like players find meaning in the arbitrary goals of a game.

Work vs. Play – The Attitude Matters: Some modern philosophies, like the FISH! philosophy used in workplaces, explicitly advocate blending play into work. They note that saying “fun is only for after work” is a flawed approach; instead, bringing a “lighthearted, playful attitude” to work tasks can increase creativity, cooperation, and satisfaction (The Importance of Fun at Work). The idea is not to shirk responsibilities, but to choose to find elements of play in them – whether it’s joking with coworkers while doing a tough job, celebrating small wins, or approaching a challenge with curiosity rather than dread. This echoes the notion that “play” is not a specific activity but a mindset. When we say someone has a playful spirit, we mean they inject enthusiasm and creativity into whatever they do. Philosophically, this viewpoint holds that life doesn’t have to be split into drudgery and fun – the two can coexist if we cultivate a mindset of finding the fun in the drudgery.

Meaning and Eudaimonia: Philosophers from Aristotle to modern thinkers distinguish between fleeting pleasure (hedonia) and deeper fulfillment (eudaimonia). While “fun” often refers to immediate pleasure, an activity can also become rewarding by being meaningful. Aristotle argued that true happiness comes from living a life of virtue and excellence (eudaimonia) – basically, finding joy in doing things well and in personal growth (How to measure happiness: hedonia vs. eudaimonia - Big Think). A task that seems unfun (say, practicing a musical instrument or studying for a degree) might not be pleasurable every moment, but if you see it contributing to your development or a larger purpose, it yields satisfaction and meaning. This perspective suggests that one way to make an unfun activity feel better is to connect it to your sense of purpose or values. For instance, cleaning the house might be reframed as caring for your family’s environment, imbuing it with relational meaning; or a dull work report could be seen as a step toward your career goals, giving it aspirational meaning. When we find personal meaning in tasks, we often experience a form of enjoyment – not giddy fun, but a contentment or pride that can carry us through the less fun parts. In practice, many people mix hedonic and eudaimonic approaches to make life’s tasks enjoyable: they seek some immediate fun (a good laugh, a gamified twist) and a sense of meaning (why this task matters in the bigger picture). Both together greatly improve our willingness to engage with “unfun” activities.

Mindfulness and Presence: Eastern philosophical traditions also offer insight. Zen Buddhism teaches finding joy in mindfulness: fully immersing oneself in the here and now of any activity. Thich Nhat Hanh, a Zen monk, famously suggested that even washing dishes can be a delightful, meaningful act if done mindfully. If you’re only washing dishes to “get it over with,” rushing to finish so you can relax, then you’re treating it as a nuisance and you “are not alive during the time you are washing the dishes,” he writes (Quote by Thich Nhat Hanh: “If while washing dishes, we think only of the c...”). Instead, if you “wash the dishes to wash the dishes,” being present with the warmth of the water and the simple motions, you may discover a sense of peace or even gratitude in the task. This perspective shifts an aversive chore into an opportunity for mindfulness, turning drudgery into a gentle, focused ritual. The philosophy here is that “boring” activities often feel unpleasant because our mind is elsewhere, resisting them. By embracing the moment – whether it’s scrubbing a plate or sweeping the floor – we remove the mental label of “boring” and simply experience it, often finding it’s not so bad or even pleasantly calming. This doesn’t make a task conventionally fun, but it does make it fulfilling and easier to enjoy, which is very much in line with turning unfun into rewarding.

Practical Strategies and Takeaways

Drawing on the above insights, here are concrete strategies to make unfun activities more fun (or at least more engaging and satisfying):

- Turn It into a Game: Gamify the activity by adding point systems, challenges, or competition. For example, give yourself points for each section of a report you write or race a timer while doing a cleaning task. If possible, involve friends/family in a friendly contest (who can declutter their room fastest, etc.). Making it game-like triggers our natural play instincts. Key idea: add rules, goals, and feedback just like a video game would. Even small rewards or goofy stakes (loser does the winner’s laundry, perhaps) can inject fun. Remember, as one philosopher put it, a game is a “voluntary attempt to overcome unnecessary obstacles,” so try imposing a fun challenge on your task (Lusory attitude - Wikipedia) (e.g. only allowing a certain number of breaks, or trying out a new technique) and treat it like a personal mission.

- Break it into Mini-Tasks: Don’t face the entire boring task in one go. Split it into smaller, bite-sized chunks with clear end points. Each time you finish a chunk, check it off or mark your progress. Psychologically, this gives you a sense of achievement and momentum. Research tip: Our brains get a dopamine hit when we achieve a goal, even a tiny one (How to make tedious tasks more tolerable | UBC Magazine). So create more achievable goals! For instance, if you have 50 math problems to do, set a goal of 5 at a time with a micro-break or fist-pump after each set. Celebrate those small wins – literally say “done!” out loud or give yourself a star. This turns a long grind into a series of satisfying mini-victories, making the process more rewarding (How to make tedious tasks more tolerable | UBC Magazine) (How to make tedious tasks more tolerable | UBC Magazine).

- Reward Yourself (Temptation Bundling): Plan a reward you really look forward to and tie it to completing the task (or a part of it). This could be as simple as “Once I finish cleaning the garage, I’ll treat myself to an episode of my favorite show or a fancy coffee.” For ongoing tasks, you can also bundle the task with something enjoyable simultaneously: e.g., only listen to a beloved podcast or playlist while doing that dull paperwork. Behavioral research shows this “temptation bundling” (combining a “want” activity with a “should” activity) increases motivation and makes the experience more pleasant ( Holding the Hunger Games Hostage at the Gym: An Evaluation of Temptation Bundling - PMC ). Over time, you might start associating a positive vibe with the chore. The key is to pick a reward that genuinely delights you and make it contingent on the task – you earn it. Knowing there’s a treat at the end (or during) can push you through initial reluctance and even make you eager to start so you can get to the fun part. Just be sure the reward doesn’t completely overshadow the task (you don’t want to only exercise to eat cake – but a little linkage can help). Done right, your brain will learn “doing X leads to something I enjoy,” which can make the task itself feel more enjoyable in anticipation of the reward (How to make tedious tasks more tolerable | UBC Magazine) (How to make tedious tasks more tolerable | UBC Magazine).

- Make It Social (or Competitive): A task done alone can feel dreary, so see if you can involve others. Invite a friend to work alongside you – even if on their own project – via a video call “work date” or in person. The company and mutual encouragement will make the time more enjoyable. You can also share your progress with others or turn it into a friendly competition: for example, agree with coworkers to each tackle a portion of boring data entry and race to finish (accuracy intact!) for bragging rights. Why this works: social connection boosts mood and accountability. Studies on gamification find that adding a social/competitive layer (like leaderboards or team challenges) significantly increases engagement and persistence (Case Studies of Successful Gamification Initiatives in Professional Development Programs ). We are social creatures – doing tedious tasks as part of a team or challenge can transform the atmosphere. Even just playing upbeat music and imagining you’re part of a collective effort can help. If in person, chatting or joking while working (so long as it doesn’t totally distract from the task) makes the time fly. Fun loves company, and a bit of peer pressure in the form of a game can push you to put in effort with a smile.

- Change the Environment: Our environment cues our mindset. Try making the setting for the task more fun or appealing. This could mean decluttering and adding some color or decorations to your workspace, playing music, or turning the chore into a themed event (e.g., “Laundry karaoke time” – fold clothes while belting out songs). Some people make a playlist of upbeat songs specifically reserved for a certain boring activity – hearing the music becomes a Pavlovian signal that “it’s time to have fun while doing X.” Others might take their work to a nicer location (if possible) – for instance, doing homework in a cozy café or well-lit library nook that they enjoy being in. The idea is to pair the dull task with a pleasant atmosphere or ritual. Even something as simple as wearing comfortable or quirky clothes while working (got a favorite silly hat?) can lighten the mood. Environment extends to tools too: using a fun pen, a cute app, or a colorful checklist can add a tiny spark of joy. These little changes can reduce the mental friction and make the activity feel “special” or novel instead of just routine.

- Attach Meaning to the Task: Take a moment to reflect why the task might matter in a broader sense – essentially, find a personal “why.” If you can see a task as connected to your goals, values, or the well-being of others, it can become more fulfilling. For example: “I’m doing this dull budgeting because it will help my family be secure and allow us a nice vacation (family happiness).” Or “This report is boring, but it’s a necessary piece in advancing my project at work, which I really care about.” Or even, “Mopping the floor is my way of showing pride in my home.” This is about reframing the narrative of the activity to emphasize its importance or benefit, which can spark intrinsic motivation. It won’t turn scrubbing toilets into a party, but it might spark a sense of purpose that makes the task feel less trivial and more rewarding. Psychologically, humans can endure a lot of hardship if they find meaning in it – here, we just apply that principle in a small way to everyday drudgery. As Aristotle and other philosophers suggest, seeing the virtue or value in what you do can transform your experience of it (How to measure happiness: hedonia vs. eudaimonia - Big Think). So, connect the dots: How does this unfun task serve you or others in the long run? The more vividly you can see that, the more satisfaction you can derive from doing it well.

- Use Mindfulness or Flow Techniques: Instead of trying to escape the task mentally, do the opposite – dive fully into it. This is the Zen approach: be present and concentrate on the details of the activity itself. Challenge yourself to do it with full attention, as if it were a skill to master or a mini-meditation. If you’re ironing clothes, for example, pay attention to the warmth of the iron, the rhythm of your movements, the smoothing of fabric. Treat it almost like a dance or an exercise in focus. By doing so, you might enter a state of flow where your mind calms and the task becomes almost automatic and peaceful. Many people find that once they get started and immerse in a repetitive task, it actually becomes relaxing (think of the satisfaction of coloring, or the calm of gardening). Mindfulness can reveal subtle enjoyable aspects of an experience that are lost when we are resisting it. Try to find one aspect you don’t mind or even like – maybe it’s the smell of the soap, or the satisfaction of seeing a clear result (a clean surface, a completed page). Staying present can transform the task from a hated chore to a form of active rest or a break from stressful thinking. As Thich Nhat Hanh teaches, “If we are washing the dishes, we should only be washing the dishes,” not rushing in our mind to the next thing (Quote by Thich Nhat Hanh: “If while washing dishes, we think only of the c...”). Approached this way, even a monotonous job can yield a small joy or at least a break from boredom, because you are making the most of the moment instead of fighting it.

- Lighten Your Attitude: Give yourself permission to have fun even while doing something serious or boring. This might mean embracing a bit of silliness: talk to yourself in an encouraging way, make a little game-time commentary (“Alright, let’s tackle this next stack of papers – we can do this!”), or find humor in the situation. Sometimes we carry an implicit belief that “if I’m not miserable, I’m not working hard enough” – challenge that! As the FISH! philosophy for workplaces says, choose your attitude: you can approach tasks with a spirit of play. For example, while doing a dull group project, crack a joke or two, or doodle a funny sketch on the whiteboard for your team. When appropriate, inject play – perhaps a 5-minute fun break every hour (a mini dance, a quick round of trivia) to keep morale up. By not taking ourselves too seriously, we reduce stress and open up space for enjoyment. Studies have found that teams that joke and have fun tend to be more productive and creative, not less, because positive mood fuels cognitive flexibility. On your own, even a smile or deliberately positive self-talk can improve your experience (it sounds corny, but it works). Essentially, be your own cheerleader or entertainer. Turning up the fun dial on your attitude can make even a dull slog feel like “not so bad, we’ve got this” instead of “this is terrible.”

- Mix It Up (Variety and Novelty): Doing the same thing the same way is a recipe for boredom. Look for ways to add variety to repeated tasks. Can you do it in a different order this time? Can you incorporate a new technique or tool? For instance, if you always study alone, try forming a study group once a week. If you typically clean the whole house in one day (and hate it), try cleaning one room each day while listening to a new genre of music each time. Novelty stimulates interest. Even swapping tasks with someone else for a while can help (maybe you hate cooking but don’t mind laundry, and your partner is vice versa – trade chores occasionally so neither of you burns out on hatred for one task). You can also gamble with tasks: randomly draw your next task from a hat to add a sense of chance or play a “roulette” with your to-do list. The element of surprise or change can break the monotony that often makes something feel unfun. Essentially, prevent the task from always feeling identical. As the saying goes, “variety is the spice of life” – it can spice up chores and routines too. By approaching the task differently or combining it with new experiences (new music, new setting, new method), you keep your brain from going on autopilot disdain and keep it engaged.

Finally, remember that making things fun is a skill in itself – one that can be practiced. Psychologists note that some people are particularly good at this (sometimes called having an “autotelic personality” – someone who can self-generate enjoyment in whatever they do). The rest of us can cultivate it by consciously applying strategies like the above. Not every method works for everyone or every task, so experiment and find what clicks for you. Maybe you’re motivated by rewards and competition, or maybe by meaning and mindfulness – likely a bit of each. The encouraging news is that even if you can’t make a task super fun, you can at least make it less aversive and more engaging by altering how you approach it. As various studies and cases have shown, our perception and context can transform our experience of an activity. What was once pure drudgery can become an interesting challenge, a social event, or a personal ritual.

In summary, fun is often something we create, not just something that happens to us. By reframing tasks, tapping into intrinsic motivations, leveraging gamification, and adopting a playful mindset, we can find enjoyment (or meaning) in activities that initially seem devoid of it. Whether it’s through small mental tricks or full-fledged game overhauls of our routines, we hold the tools to turn work into play. As one outlook teaches: “Play is not the opposite of work – it’s a way of working.” By blending play, purpose, and progress, even the “unfun” parts of life can become more rewarding – and who knows, you might even start looking forward to that once-dreaded task with a smile.

Sources:

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. – Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience (1990). [Summary of flow state and autotelic activities】 (What’s in a game?) (What’s in a game?)

- Festinger, L., & Carlsmith, J. – Cognitive dissonance study on boring tasks (1959). [Participants paid $1 vs $20 to lie about a boring task – results on perceived fun】 (The Boring Task. Taking Control of Mental Discomfort | by Valkyrie Holmes | students x students)

- Winstanley, C. – UBC research on motivation and breaking tasks into chunks (2023). [Dopamine, small wins, and rewarding yourself for effort】 (How to make tedious tasks more tolerable | UBC Magazine) (How to make tedious tasks more tolerable | UBC Magazine)

- Volkswagen “Fun Theory” experiments (2009). [Piano stairs case – 66% more stair use when made fun】 (The Piano Stairs Experiment: Making Life More Fun | Academy 4SC) (The Piano Stairs Experiment: Making Life More Fun | Academy 4SC)

- Gamification in learning/work – University of Colorado study (2012); TalentLMS report (2019). [48% engagement rise with gamified training; corporate gamification outcomes】 (Case Studies of Successful Gamification Initiatives in Professional Development Programs ) (Case Studies of Successful Gamification Initiatives in Professional Development Programs )

- Zombies, Run! app and “Zombies, Run!” – example of gamified exercise (2012). [Referenced in Bangor University piece on gamification】 (How ‘gamification’ is engaging students in learning | College of Human Sciences | Bangor University)

- Pokémon GO physical activity study – JAHA (2017). [~2000 extra steps/day and doubling of 10k-step achievers during play】 (Pokemon Go boosts physical activity, particularly among those who need it the most | Duke University School of Medicine) (Pokemon Go boosts physical activity, particularly among those who need it the most | Duke University School of Medicine)

- Foldit game – Nature/PNAS (2011). [Gamers solved an AIDS-related enzyme puzzle in 10 days via fun gameplay】 (Foldit - Wikipedia)

- Camus, A. – The Myth of Sisyphus (1942). [Philosophical perspective: “One must imagine Sisyphus happy.” Embracing the struggle】 (Existential Comic: We Must Imagine Sisyphus as Having a Hard Time Readjusting to Civilian Life | HighExistence) (Existential Comic: We Must Imagine Sisyphus as Having a Hard Time Readjusting to Civilian Life | HighExistence)

- Suits, B. – The Grasshopper: Games, Life and Utopia (1978). [Definition of playing a game as overcoming unnecessary obstacles; lusory attitude】 (Lusory attitude - Wikipedia)

- Huizinga, J. – Homo Ludens (1938). [Play as its own reward; playfulness as essential to culture】 (Homo Ludens: The Nature of Play - Communications & Society)

- Thich Nhat Hanh – The Miracle of Mindfulness (1975). [Mindfulness in dishwashing quote – being present can make any activity meaningful】 (Quote by Thich Nhat Hanh: “If while washing dishes, we think only of the c...”)

- FISH! Philosophy (Stephen Lundin et al., 1998). [“Play” at work – attitude of playfulness in everything you do】 (The Importance of Fun at Work).